Riikka Salokannel, packaging development manager at Lantmännen Unibake Finland, is behind the new breadbox packaging. The idea for the freezer packaging came up when Salokannel started looking for a bread bag material for the ”Vaasan Mestarin” bread line. The designer had become very familiar with corrugated cardboard during her career, but Salokannel had not followed the development of paper packaging materials very closely. Now Salokannel tested several different paper materials until she came across UPM AsendoTM barrier paper.

“A material was found that can be used in direct contact with food products. At the time, we didn't know if the idea would work, but it was a moment of innovation,” says Salokannel.

Frozen foods do not require as high barrier properties as some other products because freezing is a key factor in their shelf life. However, the UPM Asendo barrier paper used in the innovation also has properties that affect shelf life, such as grease and moisture barrier. The material is recyclable and compostable both industrially and in home composting.

The next step was to bring in a corrugated cardboard expert. Salokannel approached Adara Packaging, a manufacturer of corrugated cardboard and corrugated cardboard packaging, and they were interested in the project.

The first papers tried were too thin, thicker grammage weights were needed for the liner. UPM was willing to see if it was possible to make the paper more rigid. In the end, UPM Asendo barrier paper produced was a 110 g/m2.

“If the paper on the inside is thinner than the paper on the outside, it will twist the corrugated cardboard into a curve and it cannot be processed into a box. Actually, the packaging shouldn't have worked with such thin paper, but Mikko Järvinen of Adara Packaging knows how to run corrugated cardboard machinery," says Salokannel.

Accurate testing

Once the box formation was successful, Lantmännen Unibake began a year of shelf-life testing. In addition to own quality and shelf-life tests, the usability of the new packaging was verified by quality tests carried out by Foodwest.

Previously, the freezer box supplied to retailers had a large plastic bag inside.

In the shop, the amount of products needed for baking was taken from the bag and the rest was left in the bag for storage.

“The designers thought about how the new packaging would work in customers' everyday logistics. So, they set out to test the packaging on large loaves of bread,” Salokannel says.

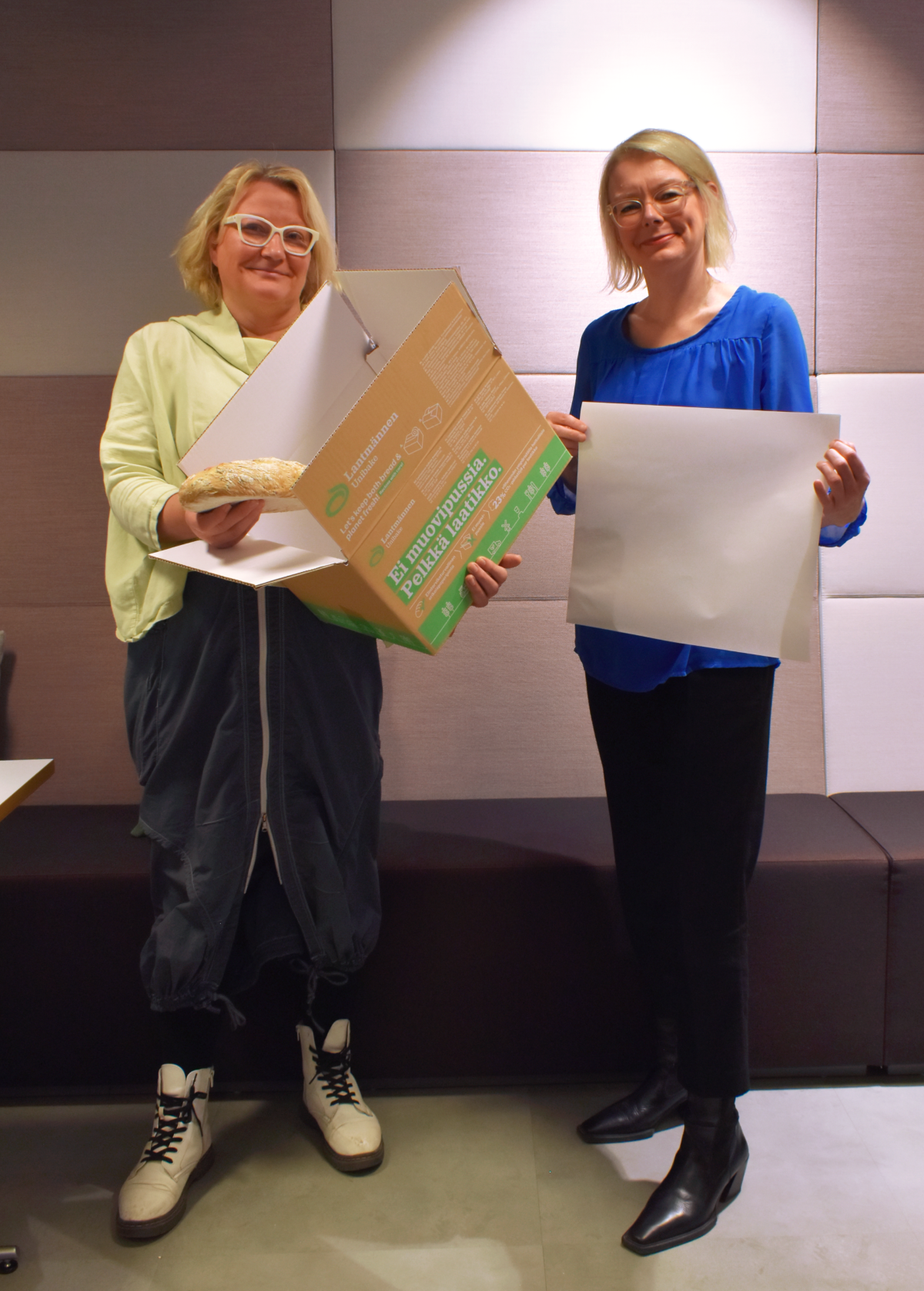

Riikka Salokannel (left) and Maarit Relander.

Whereas the corrugated cardboard box was previously a secondary packaging, the liner in the new product brings it into direct contact with the food. The packaging is certified for product safety and there are no recycled fibres, not even in the fluting. Furthermore, the brown surfaces of the corrugated cardboard are facing outwards, and the packaging clearly states that the plastic bag is missing on purpose and has not been forgotten anywhere.

“We wondered whether customers would have confidence in the food safety of the new product, but initial feedback showed no signs of distrust,” says Salokannel.

For the time being, the new solution is still slightly more expensive than the previous one, as the trial run costs are still included in the first batches. However, the materials themselves are not more expensive than before and the cost is also reduced by the elimination of the bagging stage and the EPR costs for plastics, for example.

“In liner end-use, there are a huge number of applications for the new paper. For example, it is suitable for laundry powder boxes, food trays, fruit trays, anything that does not require rigid plastic and where you want to use paper as a barrier,” says Maarit Relander, Senior Manager, Marketing at UPM Specialty Papers.

Currently, all whole loaves of bread delivered by Joutseno Bakery to Finland are packed in these new types of corrugated cardboard boxes. The next step will be to introduce this packaging method outside Finland, but first all the feedback and experience gained so far will be collected.

The power of co-creation

The packaging development project has taken about two years. It takes time to introduce new solutions because the shelf-life of products lengthens projects - after all, the tests have to be done for the whole shelf-life.

Material developers have a limit on how far they can develop a product, and they need other partners who are ready to dive in and commit to a long-term project.

“If there is no immediate momentum to introduce new products, producers need to be proactive and accept that development costs money, and that they can't get ahead of themselves,” says Salokannel.

“The whole value chain must be committed to the project,” says Relander.

“The packaging sector alone will not get projects to the finish line. The co-creation model has been valuable. It requires trust and genuine collaboration, as well as tolerance for unfinished ideas and failures,” says Salokannel.

“A product development project doesn't always go all the way, but sometimes the benefits of new inventions are obvious. As an example of a successful packaging innovation,” Salokannel recalls from her years at Sinebrychoff the 12-can “badger dog” pack, whose handle emerged from the cardboard structure. The long-fibre board replaced the cardboard previously used, resulting in clear cost savings.

“Sometimes the successes are big, sometimes the new ideas just don't work. An amusing memory from my days working at Sinebrychoff is the idea of putting beer in an aluminium bottle. However, not all chemicals work together, and the result of that product design would have been a nitroglycerine explosion. Sometimes the technology gets in the way, the machines can't handle everything,” says Salokannel.

You can't create something new without change

The new packaging solution has attracted interest from around the world. The bakeries of the international bakery company Lantmännen Unibake have several new uses for the product in different countries, and more applications are on the horizon for their own and other bakeries. Lantmännen Unibake's international product development team has been involved in testing and there is already interest in the product in at least Denmark, Norway and Belgium.

There are differences between countries in the type of frozen food they are used to. Changes in packaging may also require changes in consumer behaviour. In Sweden, raw buns are sold packaged in siliconised trays that release the product well. Design efforts have been made to ensure that fat is hardly visible on the trays.

“In Finland, we are used to the idea that a bun can stick, but will other consumers accept it? But new solutions cannot be achieved without embracing change and offering new alternatives,” says Salokannel.

Earth above

In addition to the challenges of existing packaging, consumer and regulatory demands on brand owners are often the impetus for new packaging innovations. Today, large retail chains have high sustainability targets. They want to reduce their carbon footprint, reduce plastic, and increase reusability.

“There is no smaller or larger solution that does not raise the question of whether CO2 emissions can be reduced,” says Salokannel.

New solutions must be able to be implemented without compromising quality and sustainability. According to Salokannel and Relander, renewable raw materials are a key element of sustainable packaging design. Plastics are difficult to replace in packaging and Salokannel says that the easiest solutions have already been used.

“It would be good not to have to take a drop of oil out of the ground for packaging. There are already enough greenhouse gases circulating in the atmosphere, and what we still have to produce should be used for what we need,” says Salokannel.

Article originally appeared in Pakkaus-lehti, issue 01/2024